Never Split the Difference by Chris Voss offers great tips on negotiating and influencing, all illustrated using his own experience and techniques employed during actual hostage negotiations. Voss’ stories from his time as lead hostage negotiator for the FBI read just like a Robert Ludlum novel — except they are true! Not only are the stories thrilling, but Voss’ collaborative approach to negotiating compliments our Q4 methodology at Psychological Associates. Below, we examine Voss’ negotiation strategies through a Q4 lens, and share tips for how you can use Q4 more effectively in challenging and developmental conversations.

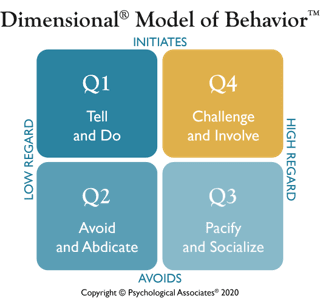

Q4 Model of Behavior

The art of negotiation relies on a keen understanding of human behavior. Here at Psychological Associates, we use the Dimensional Model of Behavior — a time-tested tool for identifying behavior in others, and adapting your own behavior to achieve superior results. While Voss does not specifically reference the Q behaviors, his descriptions and techniques map nicely onto the model.

With people exhibiting Q1 behavior, which Voss refers to as the “Assertive” type, it can be tough to get them to listen to your point of view. They tend not to listen — they don’t see any reason to do so — since they believe they already possess all the right answers. Voss points out that once Q1’s are convinced you understand them, then and only then will they listen to your point of view. Summary statements and other probes are a great way to break through and get Q1’s to listen to your views.

Alternatively, people exhibiting Q3 behavior, or “Accomodators,” pose a different challenge: they say yes to avoid conflict. Because of this, it can be hard to know if their yes is genuine commitment or conflict-avoiding appeasement. Voss suggests one way to discern the difference is to ask for the commitment 3 times in a discussion, each in a different way. For instance, the first time you ask for agreement. The second time you summarize and the negotiating partner affirms. The third time might be a question about executing the agreement. For example, “What do you see as the biggest challenge to doing this?” In Voss’ experience, it is hard to give an appeasing yes three times in one conversation. So if you get three yeses, it is likely a genuine commitment.

If someone says yes but it doesn’t seem like they are sold on it, you might probe with something like, “I hear you say yes, but it seemed like there was some hesitation in your voice.”

Finally, Never Split the Difference intriguingly shows that silence by the other person means three different things, depending on their behavior type. With Q2 behavior (which is close to Voss’ “Analyst” type), it means they want time to think. With Q3 behavior, silence means the person is angry. With Q1 behavior, it means that you don’t have anything to say, or you want them to talk.

Benefits

In our Q4 Leadership workshop, we talk about the importance of presenting benefits as a way to motivate people. Voss has a couple of interesting thoughts about benefits.

He has an interesting take on the golden rule, which he called the Black Swan Rule. It goes something like this: Don’t treat people the way you want to be treated. Rather, treat them the way they need to be treated. In other words, adapt to different behaviors differently. Don’t think that what works for you will necessarily work for someone else.

Voss also references a study from psychologist and Nobel Prize winner, Daniel Kahneman at University of Chicago. Kahneman found that averting a loss is a bigger motivator than attaining a (comparable) gain. So in framing a benefit statement, we might try pointing out what someone stands to lose if they don’t change, rather than just what they’ll gain if they do.

Probing

In Q4 Leadership we teach leaders several types of probes which can be used to better understand another person’s views. These include summary statements, reflective statements, and more. Voss’ negotiation techniques put a strong emphasis on listening, and he has interesting thoughts on how best to seek information and commitment in difficult situations.

Summary Statements

Never Split the Difference asserts that people make decisions based on emotion, and justify them with logic. As evidence, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio discovered that people with damage to the part of the brain that controls emotions were unable to make decisions. He demonstrated that showing empathy — showing someone that you understand their viewpoint — gets you farther than cold, rational arguments.

If you make a good summary statement and can elicit a “that’s right,” type comment from the other person, Voss finds that this can be transformative in moving forward in negotiations and difficult discussions. By contrast, getting a “you’re right” is not nearly as impactful. “That’s right” shows that the other person sees that you understand them. “You’re right” can be a blow off. It doesn’t signal commitment.

What’s better, positive reinforcement or empathy? Voss cites an interesting experiment with waiters carried out by psychologist, Richard Wiseman. Wiseman compared waiters that summarized back the customer’s order vs. those who gave praise and encouragement to their patrons by saying things like “great,” “sure,” “no problem…” Wiseman found that when waiters summarized people’s words back, their tips were 70% higher! This suggests the power of empathy and summary statements — that people like being understood more than they like being complimented.

Listening

Never Split the Difference surfaces four roadblocks that prevent us from listening effectively:

- We are easily distracted.

- We selectively listen, only hearing what we want to hear.

- We listen for consistency with what we already know, rather than for the truth.

- We are thinking about what we are going to say, rather than listening.

No wonder being a good listener is not easy!

Voss advocates trying to understand not just someone’s stated position, but what is behind it. What do they really want? When you understand that (through probing), you can be more successful at helping structure a solution that they buy into.

When someone seems irrational or crazy, Voss finds that they most likely aren’t. Rather, you need to probe for hidden desires, constraints, bad info they may be using, etc.

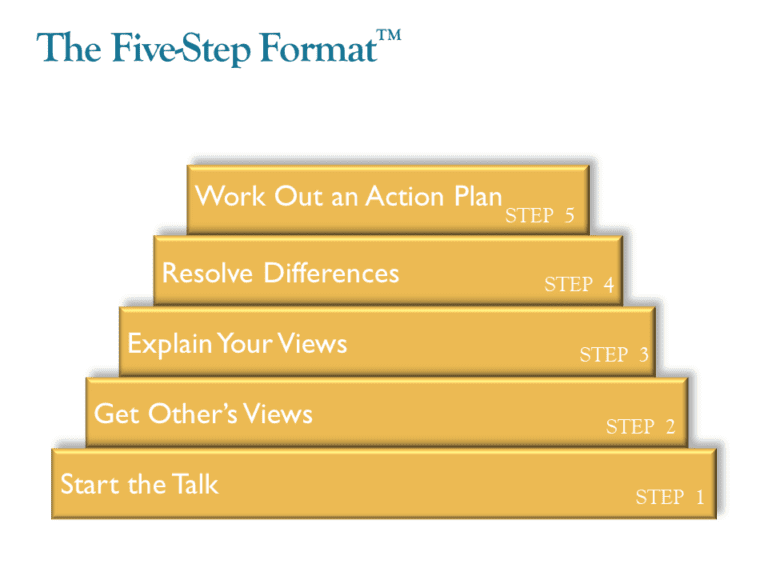

The Five-Step Format

In our Five-Step Format for a difficult conversation, Step 4, resolving differences, can be the most challenging step. Voss offers some helpful ideas here. His content on dealing with “no” and calibrated questions, was one of the most valuable parts of Never Split the Difference.

Dealing with “No”

When the other person says no, we are apt to think it is final, the end of the discussion, and we give up. Voss regards no as the start of a negotiation, not the end of it. To him, getting a no is a positive. It is a starting place for the other person’s position, enabling the negotiation to now begin in earnest. “Yes” can mean commitment, or it can mean “I’m saying yes to get you off my back.” It’s hard to distinguish between the two. With “no,” you clearly know where someone stands!

We think “no” means, “I’ve rationally considered the alternatives and made my decision.” Often, it actually means one of the following:

- I am not yet ready to agree

- You are making me feel uncomfortable

- I do not understand

- I need more info

- I want to talk it over with someone else

People say no to protect themselves. No lets them stake out an initial position, provide safety from changing circumstances, and be in control. After people say no, they are often more willing to listen and explore alternatives. Paradoxically, no is often a sign of engagement.

Voss offers some great probes to use when you get a no:

- What about this doesn’t work for you?

- What would you need to make it work?

- It seems like there’s something here that bothers you.

Voss suggests trying to get the other person to say no, as then you can start the real discussion. In terms we use here at Psychological Associates, we would check the other person’s receptivity to proceed. Instead of asking “Do you have a minute?” in hopes of a yes, Voss prefers “Is this a bad time?” to solicit a no.

Calibrated Questions

This Chris Voss concept is pure gold. If someone proposes something that you disagree with, a calibrated question:

- Is a way to say no without being disagreeable or offensive

- Gets the other person to see things from your viewpoint

- Asks for their help in working out a solution (which generates higher commitment than if you give the solution)

- Leaves the other person with a feeling of respect

- Often gets the other person to speak at length, revealing information that can help get to a solution

Voss’ classic calibrated question is, “How am I supposed to do that?” or another variation, “I’d love to help, but how am I supposed to do that?”

Other examples of calibrated questions include:

- What’s the objective? What are we trying to accomplish here?

- How can we solve this problem?

- What about this doesn’t work for you?

- What about this is important to you?

- How can I help to make this better for us?

- How would you like me to proceed?

- What is it that brought us into this situation?

- How does this look to you?

Feel free to create your own calibrated questions. Note that they tend to start with “How” or “What.” They don’t generally start with “Why,” as that can come off as accusatory.

When you are verbally attacked, don’t counterattack back, Voss recommends. Instead, pause, take a breath, and ask a calibrated question. As we say in our teamwork programs, you need to attack issues, not people. Here, Voss agrees. As he says, the person across the table is never the problem. The unsolved issue is. Focus on the issue. This helps avoid emotional escalation.

Never Split the Difference Conclusion

If you’ve enjoyed our review, you’ll love Never Split the Difference. It’s entertaining as well as educational. We hope you’ll be able to employ some of the above extensions to Q4 concepts.