Making Common Sense Common Practice

Today, change is a fact of life in any organization. The question is: Will change kill the morale and initiative of your workers, or will they respond with the creative energy needed to maintain or even improve their performance? The difference depends on skillful leaders who use common-sense methods described in these pages to produce high performance. Making Common Sense Common Practice by Drs. Vic Buzzotta, Robert Lefton, Alan Cheney, and Ann Beatty offers leaders the timely, pragmatic information they need to deal with the ever-accelerating pace of change.

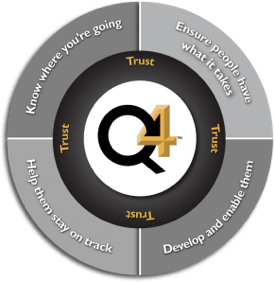

Common Sense Model

The authors unveil a common sense model. It reveals that the path to high performance has 4 areas:

- Know Where You are Going.

- Ensure People Have What It Takes.

- Develop and Enable Them.

- Help Them Stay on Track.

They show how trust ties everything together.

Common Sense is Not So Common

Why is common sense in the workplace not more common? Making Common Sense Common Practice teaches what you can do to make common sense more common and more utilized on the job.

Leadership is Common Sense

Leadership isn’t rocket science. Common sense leadership yields results. Learn how you can leverage it at your workplace.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Common Sense, Change, and Tension

Chapter 2 What Kind of Leader Should You Be?

Chapter 3 Calibrate Your Own Thermostat

Chapter 4 Know Where You Are Going

Chapter 5 Ensure People Have What It Takes

Chapter 6 Develop and Enable the Right People

Chapter 7 Help People Stay on Track

Chapter 8 Trust, the Glue that Holds It All Together

Chapter 9 The Road to High Performance

To Get Your Copy

To receive a copy of Making Common Sense Common Practice, please complete the form below.

First Chapter – Common Sense, Change, and Tension

“Common sense in an uncommon degree is what the world calls wisdom.”

-Samuel Taylor Coleridge, English Poet

Unless you have been living on another planet, you know that change best characterizes what has been happening to almost every organization over the past decade or so. Often this change has been rapid and unpredictable.

The very existence of many organizations has become dependent on their ability to compete more aggressively in the face of global competition, to be first in the marketplace to capture market share, and to reinvent themselves continually to keep up with technology.

It’s not as if change weren’t around before the ’80s, but the pace has accelerated dramatically since then. During an hour-long interview we conducted with the CEO of a Canadian-based multinational corporation, he referred to change forty-five times. “You don’t have breathing spells any more. Change is so fast that what may have worked well six months ago may not be working so well now. You’ve got to constantly assess and understand the changes occurring around you if you’re going to take rapid corrective action.”

Common Sense Capsule #1

Out of the fray has come a constant reordering of the corporate entity through divestitures, mergers, buyouts, takeovers, relocations, re-engineering, downsizing, and layoffs.

In an effort to mobilize employees and increase their efficiency to meet the crunching demands of survival, leaders have turned to a variety of methods in recent years to manage people better.

You may be discounting your best and most powerful source of reliable management wisdom-your own common sense.

His comments mirrored what was said by almost every senior executive we have talked to in more than 250 interviews at multinational corporations in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and France.

Out of the fray has come a constant reordering of the corporate entity through divestitures, mergers, buyouts, takeovers, relocations, re-engineering, downsizing, and layoffs. Along for this roller coaster ride of change has been the organization’s workforce. Every boardroom decision filters down as a people decision that must be addressed by the organization’s managers and leaders.

In an effort to mobilize employees and increase their efficiency to meet the crunching demands of survival, leaders have turned to a variety of methods in recent years to manage people better. Quality circles and total quality management programs have been launched. Empowerment and teamwork are more recent attempts to help maximize the contributions made by individuals and groups. Add to these developments the countless motivational books, tapes, lectures, and seminars devoted to improving the performance of workers.

We don’t disparage these efforts. We just feel there is an important ingredient being overlooked. As we suggested in the introduction, while searching for dramatically new and different ways to lead, you may be discounting your best and most powerful source of reliable management wisdom-your own common sense.

What are the basic commonsense principles about people and groups that you know to be true? If you can tap in to these truths, if you can take advantage of your own common sense as a guide, you can be a better leader simply by using what you already know.

For instance, it would be impossible to function if you had to approach every person you met without applying rudimentary common sense. You make choices all the time based on your “best guess” as to how people will react. Most of your common sense about others is based on an understanding of human behavior that you have assimilated through your experiences in life.

Common Sense Capsule

You can be a better leader simply by using what you already know.

The principles we will discuss are based on tested common sense.

All have been empirically verified by psychological research or in the real world of the workplace.

Most people feel empathy with others and bring an understanding about them to new situations. Even though you can recognize the ethnic, cultural, and developmental uniqueness of people, your common sense tells you that people are more alike than they are different. They respond with similar reactions and emotions to given situations.

Your own ability to predict the likely reactions of people gets to the heart of our ideas. We are inviting you to trust your common sense and pay heed to it in making leadership decisions. Unlike some of the fads and gimmicks that pass for sound leadership principles, our approach will help you confront the people problems of today, tomorrow, and next year … in spite of the pace of change.

This is true because the principles we will discuss are based on tested common sense. That is, the assumptions made about human nature have all been empirically verified by psychological research or in the real world of the workplace. They are not the product of armchair experts speculating and manufacturing catchy-sounding theories.

Because we are talking about tested common sense, we are weeding out stereotypes, biases, and prejudices. Some may mistake these for common sense, but they are not; they have not survived testing in the workplace. They have proven to be false.

While it seems logical to apply common sense, leaders often fail to make it a common practice. Let’s look at several workplace examples, all of which we have observed firsthand.

Situation

The senior executives of a U.S.-based chemical company pushed hard for employee empowerment. The executives believed it would solve all the problems created by middle management downsizing, which resulted in the average span of control rising from eight to twenty people per manager. Their direct reports were given more responsibility and encouraged to show initiative. But the results were disappointing. Their efforts seemed off the mark and unfocused.

Common Sense Capsule

Giving people the freedom to act should not mean setting them adrift.

Common sense says that leaders must help empowered workers focus their energies by providing clear direction.

Empowerment programs often fail and become regarded as just another passing “gimmick.”

Low-quality decisions abounded. Where was all that creative energy that is supposed to be unleashed when workers feel more “in charge”?

Common Sense

Giving people the freedom to act should not mean setting them adrift. Common sense says that leaders must help empowered workers focus their energies by providing clear direction. True empowerment must be accompanied by explicit objectives. In addition, employees who are “empowered” but not skilled and competent to do their jobs are likely to fail. You can’t make people excel simply by giving them the go-ahead. They must have the capability to use their new empowerment; only then will you see its advantages.

What Went Wrong?

Empowerment is not a magic word. Leaders who apply it as a quick fix neglect common sense when they give employees added responsibilities without providing strong direction. They also overlook the preparatory work they must do to make sure empowered people are competent to perform their jobs. For these reasons, empowerment programs often fail and become regarded as just another passing “gimmick” used in management. It’s a shame, because real empowerment is an excellent way for employees to develop their potential.

Situation

The U.S. subsidiary of a prominent Scandinavian heavy equipment manufacturer reorganized the production facilities by forming self-directed work teams that would operate without the typical leader. Despite teamwork training, people continued to behave as they always had. They did their parts of the job without touching base with others. They appeared to be competing with co-workers.

Common Sense Capsule

If leaders trying to promote teamwork continue to recognize only individual achievement, teamwork will suffer, if not disappear.

When change occurs, employees will be more concerned about themselves than about the firm.

Common Sense

When leaders introduce teamwork-an alternative to the traditional way of getting work done-they must change their compensation system so that it recognizes and rewards workers for the productivity of the entire team. If they continue to recognize only individual achievement, teamwork will suffer, if not disappear.

What Went Wrong?

While it is admirable for leaders to be innovative in the way they organize workers’ efforts, they must follow through and make needed adjustments throughout the system, including how they reward employees. It is just common sense that when workers are rewarded for individual achievement, they will feel they are competing with each other and avoid collaborating.

Situation

Competition from larger companies had hurt sales at a U.S.-based pharmaceutical firm, and HMO-type organizations were demanding better quality at lower prices. Management responded by re-engineering the production processes. The CEO outlined the new goals and values in a video. The new manufacturing procedures, which were supposed to result in higher quality output at lower costs, also resulted in the closing of some antiquated plants.

Instead of the expected re-energized workforce, management found many employees who appeared anxious and distracted, unable to focus on the challenges at hand. Although costs were somewhat lower, quality also dropped.

Common Sense

People tend to resist change when it threatens their security. “Is my plant the next to close?” “Are we about to be downsized?” Uncertain, fearful employees become cynical and quickly lose their sense of loyalty. Under these circumstances, productivity will most certainly decline.

Common Sense Capsule

In spite of the fact that most leaders know how important the human factor is, they let it slip for down their priorities list as the daily fire fighting overtakes them. Corporate concerns simply overwhelm their common sense.

Leaders are tempted to respond by looking for new solutions rather than simply acting on what they already know.

In the world of change, we can be certain that as organizations attempt to cope, this push-pull effect between the old and the new will produce heightened tension in the workplace.

What Went Wrong?

These executives continued making plans, expecting employees to maintain the same level of commitment to their work in spite of the ominous changes going on around them. Naturally, when change occurs, employees will be more concerned about themselves than about the firm.

These leaders should have anticipated dips in production, some defection of loyal employees, erosion of trust, and other unsettling reactions as a by-product of their actions. By doing so, they could have taken appropriate, preventive action to minimize the negative responses, where possible, before they occurred. Wishful thinking or worse, indifference, may have prevented the leaders from identifying with their workforce and seeing the changes from their perspective.

We could give other examples and will do so as we take up individual issues in coming chapters. You can see, though, the pattern of ignoring common sense in each situation. Why do leaders do this? In spite of the fact that most leaders know how important the human factor is, they let it slip far down their priorities list as the daily fire fighting overtakes them. Corporate concerns simply overwhelm their common sense. They tend to forget that so many seemingly new problems are really old ones. Leaders are tempted to respond by looking for new solutions rather than simply acting on what they already know.

Most social and economic forecasts call for a continued lack of stability in the marketplace. So, the commonsense leader must anticipate that the workforce will show a variety of predictable reactions. Some will aggressively fight change and organize resistance efforts. Others will show a dispirited acceptance of the new conditions (“Things could be worse; I still have a job”). Some people will accept early retirement. Still others will “retire” on the job.

Managing Tension

In the world of change, we can be certain that as organizations attempt to cope, this push-pull effect between the old and the new will produce heightened tension in the workplace. Is this necessarily bad? No.

Common Sense Capsule

In your leadership role, you can and should be in the business of managing the tension level of people.

When we speak of tension, we are referring to the catalyst for generating energy within any system.

Peter Senge said, “The gap between vision and current reality … is a source of energy... Indeed, the gap is the source of creative energy. We call this gap creative tension.”

Tension can either be productive or destructive, depending on its effect on people. What matters is how a particular organization and its leaders respond to tension. Why is it that one organization seems tired and immobile, its attitude toward change seemingly embalmed in apathy? How is it that another organization is frantic and distressed, its people easily derailed and almost hysterical much of the time? Why is still another organization able to take on one challenge after another, its leaders and workers energized in their enthusiasm to prevail?

We think the difference in every case is the extent to which leaders are aware of tension and are able to use common sense to regulate it. When you think about it, you can’t do a lot about the changes to which your people will be subjected. However, in your leadership role, you can and should be in the business of managing the tension level of people.

We are not using the term tension here as a synonym for stress. Stress is negative, a nonproductive feeling of anxiety and strain that surfaces when people are put under pressure for extended periods of time.

When we speak of tension, we are referring to the catalyst for generating energy within any system. Tension is present in every human being, in every species … even in entire ecosystems. When long-term environmental conditions change in the physical world, they create tension for plants and animals that ripples out like a pebble tossed in the water. Some species are obliterated. Others survive and eventually adapt to the new conditions. Surviving species evolve and even thrive as a response to the tension in the environment.

Tension also provides a catalyst in the psychological realm. In his pioneering book The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge said, “The gap between vision and current reality . . . is a source of energy. . . Indeed, the gap is the source of creative energy. We call this gap “creative tension.”1 Tension forms when a gap exists between what we have and what we need for fulfillment.

Common Sense Capsule

Research shows that too little or too much tension has the same result: sub-optimal productivity.

Between these two extremes lies an ideal level of tension.

That middle ground of optimum tension is precisely what the commonsense leader strives to maintain.

As a leader, think of yourself as the tension thermostat for your organization: Your job is to manage productivity by controlling the tension level.

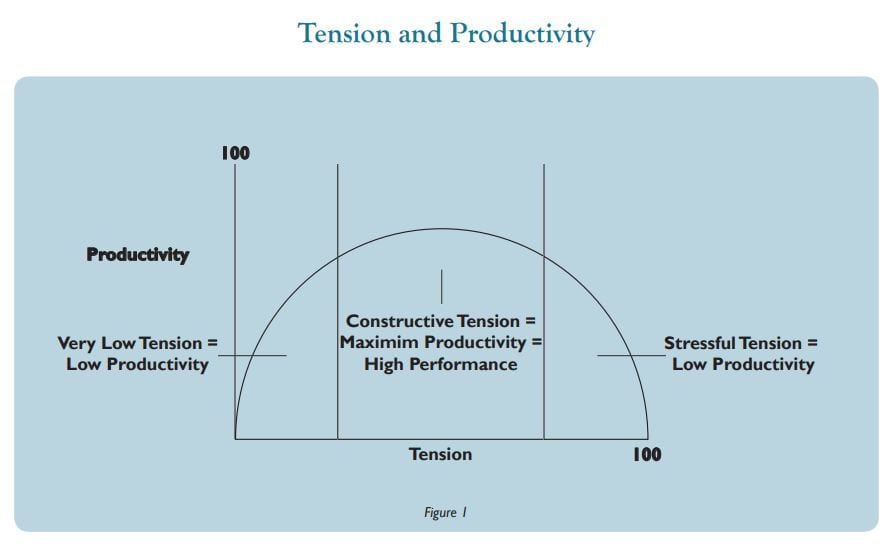

Now, apply this to the workplace. Tested common sense says that when there’s too little tension in the workplace, employees tend to relax and not take on challenges, resulting in a reduction of effort. Likewise, too much tension creates interference that can paralyze productivity. Workers are distracted by anxiety and stress and are more likely to get sick or have accidents. Research shows that too little or too much tension has the same result: sub-optimal productivity.

Regulating the Tension Thermostat

Between these two extremes lies an ideal level of tension. As psychologist Judith Bardwick says in Danger in the Comfort Zone, “We don’t get involved if the task is too easy or too hard. At its core …, creating the conditions of Earning means moving people into a middle range of risk-increasing pressure if people are stuck in Entitlement, or decreasing pressure if they are paralyzed by Fear.”2

That middle ground of optimum tension is precisely what the commonsense leader strives to maintain. He or she takes the steps needed to raise the tension when it is too low, bringing focused, creative energy back to the task. When there is too much tension, the leader knows how to lower the tension level to minimize its disruptive effects and bring it back to a positive, energizing level.

Figure 1 below shows the relationship between individual job performance and tension. When tension is too low (on the left), workers lack that reservoir of positive energy that motivates and invigorates. Constructive tension not only creates the resiliency people need to respond to change, it also largely determines how well people perform tasks. Without constructive tension and the energy associated with it, mediocrity becomes the status quo.

Too much tension (on the right) is also bad. It dissipates rather than focuses energy. The level of intensity simply turns tension into stress.

As a leader, think of yourself as the tension thermostat for your organization: Your job is to manage productivity by controlling the tension level.

Common Sense Capsule

It is a balancing act. While the right amount of tension helps people stretch, too much can break them.

Just as each individual in the organization can be gauged in terms of the tension level, so too can entire organizations. When an organization maintains a very low level of tension, employees and their leaders do not feel compelled to achieve productivity goals.

Now when you address the problems of getting the best out of workers during chaotic times, you will have a commonsense overview that crystallizes what you are really trying to accomplish-keeping tension at the optimum level (in the middle).

It is a balancing act. While the right amount of tension helps people stretch, too much can break them.

Organizations Also Have a Tension Level

Just as each individual in the organization can be gauged in terms of the tension level, so too can entire organizations. When an organization maintains a very low level of tension (on the extreme left), employees and their leaders do not feel compelled to achieve productivity goals. Jobs are fairly secure no matter how people perform. Employees can feel entitled to job benefits, which often grow lavish over time. Managers may either be aloof or completely accommodating and forgiving. They also feel little motivation to perform. Under these circumstances, no one has a desire to upset the status quo.

If you have ever dealt with or worked for a low-tension organization, one characterized by complacency, smugness, and self satisfaction, you know what we mean. Such a company can be successful as long as it has a monopoly on the market, product, or technology.

Common Sense Capsule

What are the conditions in your organization? Here are some of the things to look for: corporate strategy, resistance to change, resilience, and leadership.

However, when conditions change, when the company must compete or strive to find new markets and new customers, its people often cannot collectively summon the energy needed to reinvigorate themselves.

IBM, Kodak, British Airways, Digital Equipment, General Motors, Air France, Sears, K-Mart, NY Central Railroad, Control Data, and Pan American Airlines are all examples of organizations that, at one time or another, faltered because they were slow to respond to change. They seemed almost indifferent and apathetic about responding to the market and their competitors. Some of these organizations managed to tum themselves around while others didn’t. The life-or-death battles they waged obviously required them to redefine their strategies. They also needed to redefine their people strategies, to replace apathy with focused energy. In other words, they needed to raise the tension level of both the organization and its employees without creating disruptive tension.

What are the conditions in your organization? Here are some of the things to look for.

Corporate Strategy

Decision makers scan the horizon and see little to worry about. They continue to do what worked in the past, even though changing markets make those approaches increasingly untenable. Decision makers don’t anticipate. They don’t think about redirecting the organization, which becomes ever more slow moving and cumbersome. Inertia rules.

Resistance to Change

All organizations resist change, but low-tension ones try to smother it, since employees are largely rewarded for maintaining the status quo and are encouraged not to make waves. Thus, change is extremely threatening. That means key people in the organization will actively resist change, aided by the overstaffed bureaucracies typical of these organizations. Innovation is difficult to achieve.

Common Sense Capsule

Let’s look at the organization whose level of tension is too high.

Recent history is filled with examples of organizations that have almost come apart at the seams because of

the catastrophic impact of outside change.

Ironically, some of these organizations were originally low-tension firms unable to change fast enough to meet new marketplace demands.

Resilience

A low-tension organization that resists change for too long may become incapable of changing at all. When outside events finally force a confrontation with new realities, the result is often wrenching, sometimes catastrophic. The organization becomes too rigid to bend. Instead, it cracks, and the tension level spirals upward, sometimes out of control. At this point, the resistance to change gives way to panic and hysteria.

Leadership

Leaders of low-tension organizations have often adopted one of two management styles: hands-off/non-confrontational or coddling/accommodating. Both ignore or screen out market signals that provide early warnings that change is needed. Hands-off leaders ignore change because it may require them to make hard decisions, such as redeploying or cutting back the workforce. Coddling leaders want to protect high morale and job satisfaction so intently, they deny any evidence threatening the status quo. They won’t acknowledge intrusions on their ”big, happy family.”

Now, let’s look at the organization whose level of tension is too high (on the extreme right). As tension increases above the optimal level, stress creeps in and takes over. Why? Because a high level of tension makes employees uncertain and overwhelmed by concerns about their own skills, what’s expected of them, and how much longer their jobs will last.

You can feel the tension in these organizations! They operate in a crisis mode. Ironically, because a high stress level sometimes paralyzes workers, productivity falls below what it could be. Sensing that their efforts and abilities have no effect on the organization, that there is nothing they can do to bring tension down, employees do the defensive things people usually do under this kind of pressure. They refuse to take risks and do only what’s expected. They withdraw, thereby protecting their emotions and self-confidence from further assaults. They stop caring and shut down.

As with low-tension failures, recent history is filled with examples of organizations that have almost come apart at the seams because of the catastrophic impact of outside change.

Common Sense Capsule

High-producing organizations operate at an optimum tension level.

Tension may be high, but the leaders have it regulated.

Leaders are the regulating thermostats that keep tension at a positive peak.

Ironically, some of these organizations were originally low-tension firms unable to change fast enough to meet new marketplace demands. The airline industry is filled with such examples (Pan Am, Eastern Airlines, and others). They imploded, in a sense, sending the tension thermostat needle jumping rapidly from very low to very high. Frequently, they were characterized by leaders who, out of a sense of desperation, applied one “fix it” program after another with tired, hapless, and cynical employees caught in the middle. The result was more uncertainty and turmoil in the workplace.

High-producing organizations operate at an optimum tension level (in the middle). Their leaders have found a way to allow their people to draw a direct connection between their efforts and the productivity, profitability, and overall success of their organization. The tension level is high enough to challenge and motivate but not so high as to be stressful. People see that they earn their pay, their benefits, and job security through their own efforts, individually and collectively. They are aware of what they need to do to keep the organization competitive.

To the outsider, an organization working at the ideal tension level may look just as busy as one suffering from too much tension. The pace may be fast and very demanding. Hours may be long, and many employees may work with a round-the-clock fervor. The difference is a lack of desperation or panic. Their energy isn’t misfiring in all directions. Tension may be high, but the leaders have it regulated. They are making commonsense decisions about people so as to lead and direct their energies. They are the regulating thermostats that keep tension at a positive peak.

Notes

- Peter Senge, The Fifth Principle (New York: Currency Doubleday, 1994), 151-53.

- Judith Bardwick, Danger in the Comfort Zone (New York: Amacom, 1995), 63.

Questionnaire

Before you go on to the next chapter, think of your own situation and answer the following questions about how your organization operates. Distribute 100 points to describe your organization’s current status.

__ Q1 We believe that we must slug it out in the marketplace. We believe strong, hard-hitting promotion is more important than the quality of our products or services. With the right kind of promotion, we can sell the customer anything. We believe we’ve got to turn the heat up-way up-if we’re going to get the most from our employees. When people get burned out, we can always replace them.

__ Q2 We believe there’s not much we can do to influence the marketplace. We continue to do things pretty much as we’ve always done them, including how we reach our customers and the level of quality we build into our products and services. We try not to get our people tense and stressed out about things. We just tell them to do their jobs, don’t make waves, and everything will be OK.

__ Q3 We believe that if we have the best product or service, it will sell itself. We believe in keeping promotion and marketing efforts low-key so we don’t alienate our customers. Our people not only know that “the world will beat a path to the organization that builds a better mousetrap,” but also that contented people are happy and productive people.

__ Q4 We believe that we have to stay in touch with our market and thereby be able to adapt our product, service, and strategy to constant change. Quality of product and service must be in line with marketplace demands. We have to promote fairly and honestly with our customers. We need high-energy people who are committed to achieving the best. Our employees demonstrate both individual initiative and the collaboration required to give our customers what they want.

Ready for More?

You can obtain your copy of Making Common Sense Common Practice on Amazon or other book sites. You might also enjoy our article, Using Effective Tension to Yield Higher Workplace Productivity.